The rapidly-expanding hydrogen economy is set to be a world-wide opportunity for nuclear and for an important new route to clean energy. Taking advantage of that option will present a complex challenge for developers, writes Janet Wood, an expert author on energy issues

Hydrogen is an opportunity for nuclear but also presents challenges. (Credit: Gerd Altmann from Pixabay)

Hydrogen is already a big business. Global demand stood at 130Mt in 2020, according to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA’s) 2021 Global Hydrogen Review. Two-thirds of current production is used for industrial purposes, including producing ammonia in an early stage of fertiliser production. A third is as part of a mixture of gases, such as synthesis gas, used for fuel or feedstock for other chemicals.

At the moment, the overwhelming majority of hydrogen is produced from methane gas, via steam reforming.

Those uses are not going away – quite the reverse. In future, more industries are expected to turn to hydrogen, to replace fossil fuels in sectors such as steelmaking. Hydrogen is also expected to be important in decarbonising other sectors where electricity cannot be used, such as heavy transport including trucking and rail services. It is also an important option for long-term energy storage and other roles in managing electricity supply (eg hydrogen replacing methane in gas turbines). The IEA estimates that by 2050 hydrogen production will have to grow to over 500 Mt annually. The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission puts the potential at twice that: 100 Mt.

But in order to play those roles hydrogen must be produced free of carbon emissions. Two options are on the table. The traditional method of methane reforming uses steam at 700–1,000°C to produce hydrogen (an alternative method, autothermal reforming – is a chemical process that has not yet been deployed at scale). In order to qualify as low carbon it has to be combined with carbon capture and storage, increasing the cost and risk of deployment. Another problem in stepping up the use of methane reforming is the significant constituency across climate and energy who consider that basing a hydrogen industry on the continued use of methane can only be a short-term fix.

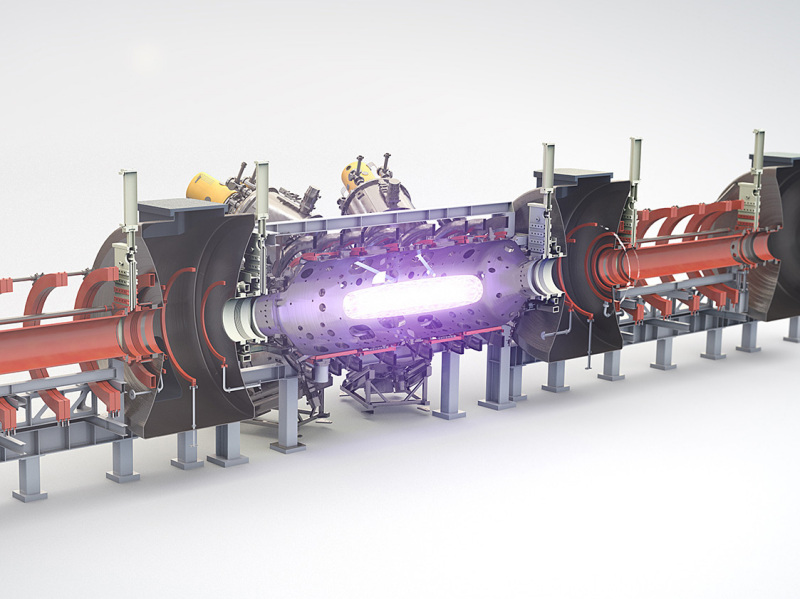

There is growing interest in electrolysers, which use an electric cell to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. They have the attraction of simplicity, if the electricity used is low carbon (ie produced by nuclear or renewables) and is now being installed at the demonstration or pre-commercial scale (up to a few megawatts) at sites worldwide.

In electrolysis, a lot of power capacity is of course required. The IEA estimates that meeting its hydrogen target will require that installed electrolysis capacity reaches around 850GW by 2030 and almost 3,600GW by 2050. That figure is likely an underestimate: the dedicated plant may be used, but also electrolysers are likely to be used intermittently, at times when there is an excess generation – raising the overall capacity requirement.

But both methane reforming and electrolysis place other demands on the system – for heat, gas and, crucially, water. A ‘whole system’ view reveals some of the benefits, and also the complexity, of combining nuclear and hydrogen infrastructure.

Heat, natural gas and water are key inputs, and when it comes to outputs it is not enough to produce hydrogen; it must also be delivered to its users.

How does the nuclear-hydrogen nexus fit together in practice?

Great Britain is an interesting test bed for this discussion, as there is political support for both a fleet of new reactors and a switch to hydrogen to decarbonise industry and transport. It has announced an ambition for a dozen new reactors and it has provided research and development funding for hydrogen production and use. These are focused on several existing ‘industrial clusters’ in coastal areas. Finally, GB is a relatively small area (and for this purpose Scotland, which has outlawed new nuclear, can be excluded) so potential sites are relatively close (tens rather than hundreds of miles). Although electricity can obviously be transported across the country to power electrolysers, nuclear’s key heat offering (see below) cannot be transported in the same way. Even for electricity, limited grid capacity is already causing huge constraint costs and building a new network is a slow and costly process. That means siting issues are make or break for nuclear’s role as a hydrogen producer.

Sizewell, on the southeast coast, is a useful example, as development consent was recently granted for a new reactor, Sizewell C, at the site. EDF has previously signalled hydrogen as a potential byproduct at Sizewell C.

Sizewell is the site for a new nuclear power station already earmarked for possible hydrogen production. (Credit: GOV.UK/Wikimedia Commons)

Heat

Beyond electrical power, nuclear’s ability to generate even larger quantities of heat also offers an opportunity in hydrogen production.

Heat is crucial for steam methane reforming, as the name implies. In the current deployment, the heat is supplied using additional gas to create steam. That has the benefit of simplicity but it increases gas consumption by up to a third so alternate heat sources are attractive.

But it is electrolysis where the availability of high-temperature steam is a game-changer. Increasing the temperature at which electrolysis takes place increases the process efficiency significantly – from around 40% at 100degC to around 60% efficiency at 850degC. The still higher temperatures are available from nuclear offer another option: high-temperature steam electrolysis, which splits hydrogen and oxygen out from steam instead of water at temperatures towards 100deg C, increasing hydrogen production efficiency to around the 80% level.

Using electricity from nuclear to produce hydrogen is relatively flexible on siting as it can be transmitted across the country. Using nuclear’s heat is the opposite: practically, it cannot be transported long distances.

Water stresses

Currently, according to PA Consulting, for the two dominant electrolysers commercially available (alkaline and proton-electron membrane technologies) water use is 9-14kg per kg of hydrogen produced (depending on the amount of demineralisation required), with some estimates as high as 18kg. Methane reforming requires 6-13kg of water per kg of hydrogen produced. To put it another way, a typical estimate is that when working consistently a 1MW electrolyser will produce around 400kg of hydrogen per day. That suggests water use of 3.6-5.2 cubic meters per day.

At Sizewell, EDF’s enthusiasm for hydrogen has cooled because of problems in meeting the water demand at the site.

At 800 cubic metres per day, Sizewell B’s fresh water requirement is dwarfed by its seawater demand (50 cubic metres a second) but it still represents about 7 per cent of clean water demand in the local catchment area. Sizewell C will have a larger freshwater demand of around 2000 cubic metres per day.

Despite GB’s rainy reputation, the east and south of the country are referred to as ‘water stressed’ areas by environmental regulator the Environment Agency. To meet Sizewell C’s freshwater needs EDF had planned to install a pipeline to abstract water from the River Waveney, 18km away. However, the local water company, Essex and Suffolk Water anticipate that the area will be in “water deficit” by the time Sizewell C is operating in the 2040s and it expects that the Environment Agency will reduce its abstraction licence from the River Waveney to less than half its current level by that time. Sizewell C has another option to meet the power plant’s water requirements, which is to build a desalination plant so it can use seawater instead – an option that has already run into opposition. That makes abstracting more water for hydrogen production problematic. A commercial-sized electrolyser rated at more than 100MW could double the site’s demand for fresh water.

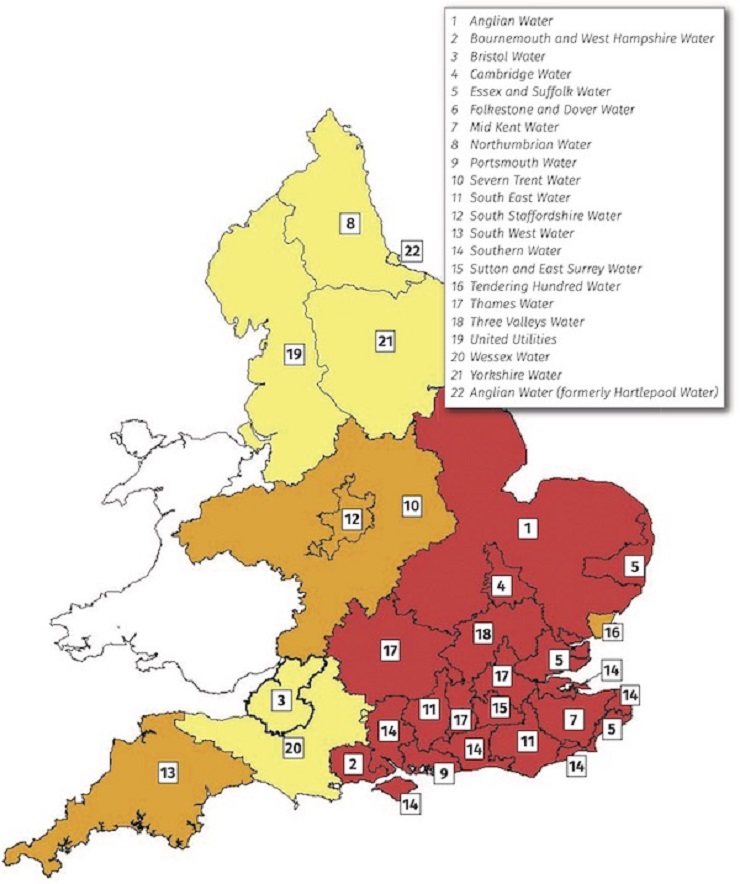

Several other nuclear sites in GB are also in ‘water stressed’ areas – typically those in the south and east of the country (see map). But the UK’s Climate Change Committee foresees those areas expanding in future unless there are substantial changes in water use.

UK Environment Agency map shows just how water-stressed parts of the country are. (Credit: UK Environment Agency)

The IEA says using seawater is an alternative in coastal areas, using reverse osmosis for desalination. The IEA quoted an electricity demand of up to 4kWh per cubic meter of water and an increase in total hydrogen production costs of $0.01–0.02/kgH2 if desalination is required. This is far from impossible on these grounds, but onshore desalination raises environmental questions in disposing of the brine produced alongside the desalinated water.

(The equation is different for producing hydrogen at offshore wind sites and piping it onshore, as has been proposed elsewhere. There is no option of using local freshwater so desalination is required, but disposal of the brine offshore is less problematic.)

Pipeline issues

While water supplies have been a siting issue for nuclear plants in the past, and so has the potential for heat customers, nuclear developers have not needed to consider the availability of gas transport infrastructure in the past. That changes if nuclear is to be used as a major hydrogen producer.

Using nuclear heat to boost methane reforming requires the site to have access to gas supplies for the long term. Electrolysis of course does not require gas input. But both options require gas export infrastructure. Today, hydrogen is transported from the point of production to the point of use via pipeline and over the road in cryogenic liquid tanker trucks or gaseous tube trailers. Pipelines are deployed in regions with substantial demand (hundreds of tons per day) that are expected to remain stable for decades. This means that hydrogen producers using the methane reforming route have to be sure that the gas assets they are using will have a methane supply in the long term – which excludes pipes that may be converted to transporting hydrogen. Effectively that places methane reformers close to methane import terminals.

All this adds up to a more complex siting challenge for new nuclear plants that see a future in producing hydrogen alongside (or instead of) power – and for different customers. Gas, water, hydrogen and heat requirements all have to be met at sites that also meet nuclear restrictions.

In Great Britain, a comparison of the existing gas network, industrial clusters and existing nuclear sites superficially shows some consistency (see maps). But zoom in and a more complex picture emerges. HyNET in the northwest is a hydrogen growth area with a variety of users. It is also well served by the gas network, in an area where repurposing it for hydrogen transport is under consideration. But the nearest existing nuclear site is Heysham, around 60 miles away with large urban centres such as Liverpool in between.

Heysham is near the UK’s northwest hydrogen hub Hynet, but it’s still too far to transport heat. (Credit: Rwendland/Wikimedia Commons)

Some of these tensions will be reduced by using new nuclear options. Smaller reactors will have smaller water footprints. But they also produce less hydrogen and smaller volumes in turn limit hydrogen transport options, as there is a point at which pipelines become uneconomic. Local hydrogen consumers will be required, along with a way to manage an intermittent hydrogen supply, if the ‘local’ reactor has other electricity customers.

Other sites such as those on the south or east coast are much further away from both resources and consumers.

The UK’s current nuclear planning framework largely restricts new nuclear to existing sites. In fact, the framework has lapsed and a new siting framework is expected. That could open up new sites, although the UK has previously found it difficult to expand its nuclear site pool beyond those already existing.

None of these types of issues is new to electricity asset managers. Combined heat and power projects, for example, routinely manage heat and electricity customers and may include a heat store to provide flexibility. The problem of limited water supplies is well known, at least to inland nuclear operators who rely on river water for cooling.

But the uncertainties involved in the hydrogen option will present new challenges to nuclear investors.