In the coming decades, renewable energy sources such as solar and wind will increasingly dominate the conventional power grid. Because those sources only generate electricity when it's sunny or windy, ensuring a reliable grid—one that can deliver power 24/7—requires some means of storing electricity when supplies are abundant and delivering it later when they're not. And because there can be hours and even days with no wind, for example, some energy storage devices must be able to store a large amount of electricity for a long time.

A promising technology for performing that task is the flow battery, an electrochemical device that can store hundreds of megawatt-hours of energy—enough to keep thousands of homes running for many hours on a single charge. Flow batteries have the potential for long lifetimes and low costs in part due to their unusual design. In the everyday batteries used in phones and electric vehicles, the materials that store the electric charge are solid coatings on the electrodes.

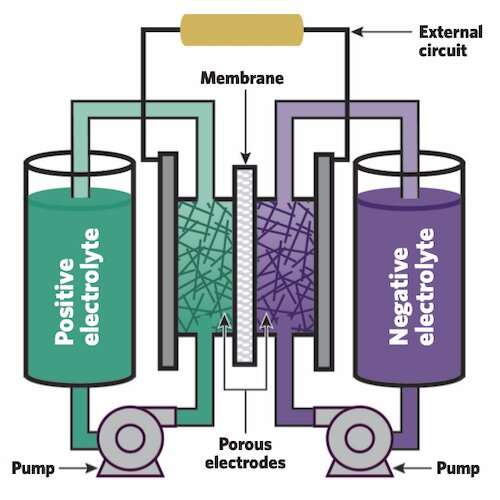

"A flow battery takes those solid-state charge-storage materials, dissolves them in electrolyte solutions, and then pumps the solutions through the electrodes," says Fikile Brushett, an associate professor of chemical engineering at MIT. That design offers many benefits and poses a few challenges.

Flow batteries: Design and operation

A flow battery contains two substances that undergo electrochemical reactions in which electrons are transferred from one to the other. When the battery is being charged, the transfer of electrons forces the two substances into a state that's "less energetically favorable" as it stores extra energy. (Think of a ball being pushed up to the top of a hill.) When the battery is being discharged, the transfer of electrons shifts the substances into a more energetically favorable state as the stored energy is released. (The ball is set free and allowed to roll down the hill.)

At the core of a flow battery are two large tanks that hold liquid electrolytes, one positive and the other negative. Each electrolyte contains dissolved "active species"—atoms or molecules that will electrochemically react to release or store electrons. During charging, one species is "oxidized" (releases electrons), and the other is "reduced" (gains electrons); during discharging, they swap roles. Pumps are used to circulate the two electrolytes through separate electrodes, each made of a porous material that provides abundant surfaces on which the active species can react. A thin membrane between the adjacent electrodes keeps the two electrolytes from coming into direct contact and possibly reacting, which would release heat and waste energy that could otherwise be used on the grid.

When the battery is being discharged, active species on the negative side oxidize, releasing electrons that flow through an external circuit to the positive side, causing the species there to be reduced. The flow of those electrons through the external circuit can power the grid. In addition to the movement of the electrons, "supporting" ions—other charged species in the electrolyte—pass through the membrane to help complete the reaction and keep the system electrically neutral.

Once all the species have reacted and the battery is fully discharged, the system can be recharged. In that process, electricity from wind turbines, solar farms, and other generating sources drives the reverse reactions. The active species on the positive side oxidize to release electrons back through the wires to the negative side, where they rejoin their original active species. The battery is now reset and ready to send out more electricity when it's needed. Brushett adds, "The battery can be cycled in this way over and over again for years on end."

Benefits and challenges

A major advantage of this system design is that where the energy is stored (the tanks) is separated from where the electrochemical reactions occur (the so-called reactor, which includes the porous electrodes and membrane). As a result, the capacity of the battery—how much energy it can store—and its power—the rate at which it can be charged and discharged—can be adjusted separately. "If I want to have more capacity, I can just make the tanks bigger," explains Kara Rodby Ph.D. '22, a former member of Brushett's lab and now a technical analyst at Volta Energy Technologies. "And if I want to increase its power, I can increase the size of the reactor." That flexibility makes it possible to design a flow battery to suit a particular application and to modify it if needs change in the future.

However, the electrolyte in a flow battery can degrade with time and use. While all batteries experience electrolyte degradation, flow batteries in particular suffer from a relatively faster form of degradation called "crossover." The membrane is designed to allow small supporting ions to pass through and block the larger active species, but in reality, it isn't perfectly selective. Some of the active species in one tank can sneak through (or "cross over") and mix with the electrolyte in the other tank. The two active species may then chemically react, effectively discharging the battery. Even if they don't, some of the active species is no longer in the first tank where it belongs, so the overall capacity of the battery is lower.

Recovering capacity lost to crossover requires some sort of remediation—for example, replacing the electrolyte in one or both tanks or finding a way to reestablish the "oxidation states" of the active species in the two tanks. (Oxidation state is a number assigned to an atom or compound to tell if it has more or fewer electrons than it has when it's in its neutral state.) Such remediation is more easily—and therefore more cost-effectively—executed in a flow battery because all the components are more easily accessed than they are in a conventional battery.

The state of the art: Vanadium

A critical factor in designing flow batteries is the selected chemistry. The two electrolytes can contain different chemicals, but today the most widely used setup has vanadium in different oxidation states on the two sides. That arrangement addresses the two major challenges with flow batteries.

First, vanadium doesn't degrade. "If you put 100 grams of vanadium into your battery and you come back in 100 years, you should be able to recover 100 grams of that vanadium—as long as the battery doesn't have some sort of a physical leak," says Brushett.

And second, if some of the vanadium in one tank flows through the membrane to the other side, there is no permanent cross-contamination of the electrolytes, only a shift in the oxidation states, which is easily remediated by re-balancing the electrolyte volumes and restoring the oxidation state via a minor charge step. Most of today's commercial systems include a pipe connecting the two vanadium tanks that automatically transfers a certain amount of electrolyte from one tank to the other when the two get out of balance.

However, as the grid becomes increasingly dominated by renewables, more and more flow batteries will be needed to provide long-duration storage. Demand for vanadium will grow, and that will be a problem. "Vanadium is found around the world but in dilute amounts, and extracting it is difficult," says Rodby. "So there are limited places—mostly in Russia, China, and South Africa—where it's produced, and the supply chain isn't reliable." As a result, vanadium prices are both high and extremely volatile—an impediment to the broad deployment of the vanadium flow battery.

Beyond vanadium

The question then becomes: If not vanadium, then what? Researchers worldwide are trying to answer that question, and many are focusing on promising chemistries using materials that are more abundant and less expensive than vanadium. But it's not that easy, notes Rodby. While other chemistries may offer lower initial capital costs, they may be more expensive to operate over time. They may require periodic servicing to rejuvenate one or both of their electrolytes. "You may even need to replace them, so you're essentially incurring that initial (low) capital cost again and again," says Rodby.

Indeed, comparing the economics of different options is difficult because "there are so many dependent variables," says Brushett. "A flow battery is an electrochemical system, which means that there are multiple components working together in order for the device to function. Because of that, if you are trying to improve a system—performance, cost, whatever—it's very difficult because when you touch one thing, five other things change."

So how can we compare these new and emerging chemistries—in a meaningful way—with today's vanadium systems? And how do we compare them with one another, so we know which ones are more promising and what the potential pitfalls are with each one? "Addressing those questions can help us decide where to focus our research and where to invest our research and development dollars now," says Brushett.

Techno-economic modeling as a guide

A good way to understand and assess the economic viability of new and emerging energy technologies is using techno-economic modeling. With certain models, one can account for the capital cost of a defined system and—based on the system's projected performance—the operating costs over time, generating a total cost discounted over the system's lifetime. That result allows a potential purchaser to compare options on a "levelized cost of storage" basis.

Using that approach, Rodby developed a framework for estimating the levelized cost for flow batteries. The framework includes a dynamic physical model of the battery that tracks its performance over time, including any changes in storage capacity. The calculated operating costs therefore cover all services required over decades of operation, including the remediation steps taken in response to species degradation and crossover.

Analyzing all possible chemistries would be impossible, so the researchers focused on certain classes. First, they narrowed the options down to those in which the active species are dissolved in water. "Aqueous systems are furthest along and are most likely to be successful commercially," says Rodby. Next, they limited their analyses to "asymmetric" chemistries; that is, setups that use different materials in the two tanks. (As Brushett explains, vanadium is unusual in that using the same "parent" material in both tanks is rarely feasible.) Finally, they divided the possibilities into two classes: species that have a finite lifetime and species that have an infinite lifetime; that is, ones that degrade over time and ones that don't.

Results from their analyses aren't clear-cut; there isn't a particular chemistry that leads the pack. But they do provide general guidelines for choosing and pursuing the different options.

Finite-lifetime materials

While vanadium is a single element, the finite-lifetime materials are typically organic molecules made up of multiple elements, among them carbon. One advantage of organic molecules is that they can be synthesized in a lab and at an industrial scale, and the structure can be altered to suit a specific function. For example, the molecule can be made more soluble, so more will be present in the electrolyte and the energy density of the system will be greater; or it can be made bigger so it won't fit through the membrane and cross to the other side. Finally, organic molecules can be made from simple, abundant, low-cost elements, potentially even waste streams from other industries.

Despite those attractive features, there are two concerns. First, organic molecules would probably need to be made in a chemical plant, and upgrading the low-cost precursors as needed may prove to be more expensive than desired. Second, these molecules are large chemical structures that aren't always very stable, so they're prone to degradation. "So along with crossover, you now have a new degradation mechanism that occurs over time," says Rodby. "Moreover, you may figure out the degradation process and how to reverse it in one type of organic molecule, but the process may be totally different in the next molecule you work on, making the discovery and development of each new chemistry require significant effort."

Research is ongoing, but at present, Rodby and Brushett find it challenging to make the case for the finite-lifetime chemistries, mostly based on their capital costs. Citing studies that have estimated the manufacturing costs of these materials, Rodby believes that current options cannot be made at low enough costs to be economically viable. "They're cheaper than vanadium, but not cheap enough," says Rodby.

The results send an important message to researchers designing new chemistries using organic molecules: Be sure to consider operating challenges early on. Rodby and Brushett note that it's often not until way down the "innovation pipeline" that researchers start to address practical questions concerning the long-term operation of a promising-looking system. The MIT team recommends that understanding the potential decay mechanisms and how they might be cost-effectively reversed or remediated should be an upfront design criterion.

Infinite-lifetime species

The infinite-lifetime species include materials that—like vanadium—are not going to decay. The most likely candidates are other metals; for example, iron or manganese. "These are commodity-scale chemicals that will certainly be low cost," says Rodby.

Here, the researchers found that there's a wider "design space" of feasible options that could compete with vanadium. But there are still challenges to be addressed. While these species don't degrade, they may trigger side reactions when used in a battery. For example, many metals catalyze the formation of hydrogen, which reduces efficiency and adds another form of capacity loss. While there are ways to deal with the hydrogen-evolution problem, a sufficiently low-cost and effective solution for high rates of this side reaction is still needed.

In addition, crossover is a still a problem requiring remediation steps. The researchers evaluated two methods of dealing with crossover in systems combining two types of infinite-lifetime species.

The first is the "spectator strategy." Here, both of the tanks contain both active species. Explains Brushett, "You have the same electrolyte mixture on both sides of the battery, but only one of the species is ever working and the other is a spectator." As a result, crossover can be remediated in similar ways to those used in the vanadium flow battery. The drawback is that half of the active material in each tank is unavailable for storing charge, so it's wasted. "You've essentially doubled your electrolyte cost on a per-unit energy basis," says Rodby.

The second method calls for making a membrane that is perfectly selective: It must let through only the supporting ion needed to maintain the electrical balance between the two sides. However, that approach increases cell resistance, hurting system efficiency. In addition, the membrane would need to be made of a special material—say, a ceramic composite—that would be extremely expensive based on current production methods and scales. Rodby notes that work on such membranes is under way, but the cost and performance metrics are "far off from where they'd need to be to make sense."

Time is of the essence

The researchers stress the urgency of the climate change threat and the need to have grid-scale, long-duration storage systems at the ready. "There are many chemistries now being looked at," says Rodby, "but we need to home in on some solutions that will actually be able to compete with vanadium and can be deployed soon and operated over the long term."

The techno-economic framework is intended to help guide that process. It can calculate the levelized cost of storage for specific designs for comparison with vanadium systems and with one another. It can identify critical gaps in knowledge related to long-term operation or remediation, thereby identifying technology development or experimental investigations that should be prioritized. And it can help determine whether the trade-off between lower upfront costs and greater operating costs makes sense in these next-generation chemistries.

The good news, notes Rodby, is that advances achieved in research on one type of flow battery chemistry can often be applied to others. "A lot of the principles learned with vanadium can be translated to other systems," she says. She believes that the field has advanced not only in understanding but also in the ability to design experiments that address problems common to all flow batteries, thereby helping to prepare the technology for its important role of grid-scale storage in the future.